2020. 2. 9. 02:43ㆍ카테고리 없음

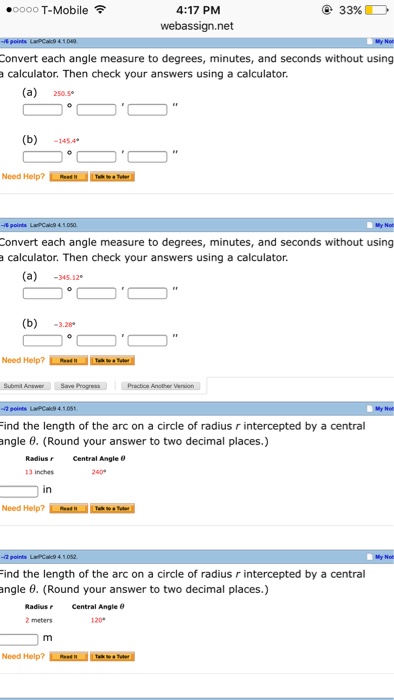

Students learning will include understanding common measurements using angles in degrees, minutes, and seconds and decimal degree. Make conversions from decimal degree to degree, minutes, and seconds. Students will also learn to plot a property line using bearings inside a circle. If we extended the line between angles a and b and we drew a line through the tip of angle. Measuring the Angles of Triangles: 180 Degrees Related. Just a few seconds while we find the right.

There are two commonly used units of measurement for angles. The more familiar unit of measurement is that of degrees.

A circle is divided into 360 equal degrees, so that a right angle is 90°. For the time being, we’ll only consider angles between 0° and 360°, but later, in the section on trigonometric functions, we’ll consider angles greater than 360° and negative angles. Degrees may be further divided into minutes and seconds, but that division is not as universal as it used to be. Each degree is divided into 60 equal parts called minutes. So seven and a half degrees can be called 7 degrees and 30 minutes, written 7° 30'.

Each minute is further divided into 60 equal parts called seconds, and, for instance, 2 degrees 5 minutes 30 seconds is written 2° 5' 30'. The division of degrees into minutes and seconds of angle is analogous to the division of hours into minutes and seconds of time. Parts of a degree are now usually referred to decimally. For instance seven and a half degrees is now usually written 7.5°. When a single angle is drawn on a xy-plane for analysis, we’ll draw it in standard position with the vertex at the origin (0,0), one side of the angle along the x-axis, and the other side above the x-axis. Radians The other common measurement for angles is radians.

For this measurement, consider the unit circle (a circle of radius 1) whose center is the vertex of the angle in question. Then the angle cuts off an arc of the circle, and the length of that arc is the radian measure of the angle. It is easy to convert between degree measurement and radian measurement. The circumference of the entire circle is 2 π, so it follows that 360° equals 2 π radians. Hence, 1° equals π/180 radians and 1 radian equals 180/ π degrees Most calculators can be set to use angles measured with either degrees or radians. Be sure you know what mode your calculator is using. Short note on the history of radians Although the word “radian” was coined by Thomas Muir and/or James Thompson about 1870, mathematicians had been measuring angles that way for a long time.

For instance, Leonhard Euler (1707–1783) in his Elements of Algebra explicitly said to measure angles by the length of the arc cut off in the unit circle. That was necessary to give his famous formula involving complex numbers that relates the sign and cosine functions to the exponential function e iθ = cos θ + i sin θ where θ is what was later called the radian measurment of the angle. Unfortunately, an explanation of this formula is well beyond the scope of these notes.

But, for a little more information about complex numbers, see my. Radians and arc length An alternate definition of radians is sometimes given as a ratio. Instead of taking the unit circle with center at the vertex of the angle θ, take any circle with center at the vertex of the angle. Then the radian measure of the angle is the ratio of the length of the subtended arc to the radius r of the circle.

For instance, if the length of the arc is 3 and the radius of the circle is 2, then the radian measure is 1.5. The reason that this definition works is that the length of the subtended arc is proportional to the radius of the circle. In particular, the definition in terms of a ratio gives the same figure as that given above using the unit circle. This alternate definition is more useful, however, since you can use it to relate lengths of arcs to angles. The length of an arc is is the radius r times the angle θ where the angle is measured in radians. For instance, an arc of θ = 0.3 radians in a circle of radius r = 4 has length 0.3 times 4, that is, 1.2.

Radians and sector area A sector of a circle is that part of a circle bounded by two radii and the arc of the circle that joins their ends. The area of this sector is easy to compute from the radius r of the circle and the angle θ beween the radii when it’s measured in radians. Since the area of the whole circle is πr 2, and the sector is to the whole circle as the angle θ is to 2 π, therefore Common angles Below is a table of common angles in both degree measurement and radian measurement.

Note that the radian measurement is given in terms of π. It could, of course, be given decimally, but radian measurement often appears with a factor of π. Angle Degrees Radians 90° π/2 60° π/3 45° π/4 30° π/6 Exercises Edwin S. Crawley wrote a book One Thousand Exercises in Plane and Spherical Trigonometry, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1914. The problems in this short course are taken from that text (but not all 1000 of them!) He gave his problems with up to five digits of accuracy, so students had to work some time to solve them, and they used tables of logarithms to help in multiplication and division. Students had to be able to use the sine-cosine table, the tangent table, the logarithm table, the log-sin-cos table, and the log-tan table. Now we can use calculators!

That means you can concentrate on the concepts and not on laborious computations. Crawley didn’t used decimal notation for fractions of a degree, but minutes and seconds. Each set of exercises includes first the statements of the exercises, second some hints to solve the exercises, and third the answer to the exercises. Express the following angles in radians. 12 degrees, 28 minutes, that is, 12° 28'. Reduce the following numbers of radians to degrees, minutes, and seconds. Given the angle a and the radius r, to find the length of the subtending arc.

A = 0° 17' 48', r = 6.2935. A = 121° 6' 18', r = 0.2163. Given the length of the arc l and the radius r, to find the angle subtended at the center. L =.16296, r = 12.587. L = 1.3672, r = 1.2978. Given the length of the arc l and the angle a which it subtends at the center, to find the radius. A = 0° 44' 30', l =.032592.

A Line With Angles Not Straight

A = 60° 21' 6', l =.4572. Find the length to the nearest inch of a circular arc of 11 degrees 48.3 minutes if the radius is 3200 feet.

A railroad curve forms a circular arc of 9 degrees 36.7 minutes, the radius to the center line of the track being 2100 feet. If the gauge is 5 feet, find the difference in length of the two rails to the nearest half-inch. How much does one change latitude by walking due north one mile, assuming the earth to be a sphere of radius 3956 miles? Compute the length in feet of one minute of arc on a great circle of the earth.

How long is the length of one second of arc? On a circle of radius 5.782 meters the length of an arc is 1.742 meters. What angle does it subtend at the center? A balloon known to be 50 feet in diameter subtends at the eye an angle of 8 1/2 minutes. How far away is it?

To convert degrees to radians, first convert the number of degrees, minutes, and seconds to decimal form. Divide the number of minutes by 60 and add to the number of degrees. So, for example, 12° 28' is 12 + 28/60 which equals 12.467°. Next multiply by π and divide by 180 to get the angle in radians. Conversely, to convert radians to degrees divide by π and multiply by 180. So, 0.47623 divided by π and multiplied by 180 gives 27.286°.

You can convert the fractions of a degree to minutes and seconds as follows. Multiply the fraction by 60 to get the number of minutes.

Here, 0.286 times 60 equals 17.16, so the angle could be written as 27° 17.16'. Then take any fraction of a minute that remains and multiply by 60 again to get the number of seconds. Here, 0.16 times 60 equals about 10, so the angle can also be written as 27° 17' 10'.

In order to find the length of the arc, first convert the angle to radians. For 3(a), 0°17'48' is 0.0051778 radians. Then multiply by the radius to find the length of the arc.

To find the angle, divide by the radius. That gives you the angle in radians. That can be converted to degrees to get Crawley’s answers. As mentioned above, radian measure times radius = arc length, so, using the letters for this problem, ar = l, but a needs to be converted from degree measurement to radian measurement first. So, to find the radius r, first convert the angle a to radians, then divide that into the length l of the arc. Arc length equals radius times the angle in radians. It helps to draw the figure.

The radius to the outer rail is 2102.5 while the radius to the inner rail is 2097.5. You’ve got a circle of radius 3956 miles and an arc of that circle of length 1 mile. What is the angle in degrees? (The mean radius of the earth was known fairly accurately in 1914. See if you can find out what Eratosthenes thought the radius of the earth was back in the third century B.C.E.) 10. A minute of arc is 1/60 of a degree. Convert to radians.

The radius is 3956. What is the length of the arc?

Since the length of the arc equals radius times the angle in radians, it follows that the angle in radians equals the length of the arc divided by the radius. It’s easy to convert radians to degrees. Imagine that the diameter of the balloon is a part of an arc of a circle with you at the center. (It isn’t exactly part of the arc, but it’s pretty close.) That arc is 50 feet long. You know the angle, so what is the radius of that circle? 2.1137 times 0.2163 equals 0.4572. 0.16296/12.587 = 0.012947 radians = 0° 44' 30'.

1.3672/1.2978 = 1.0535 radians = 60.360° = 60° 21.6' = 60° 21' 35'. Ra = (3200') (0.20604) = 659.31' = 659' 4'. The angle a = 0.16776 radians. The difference in the lengths is 2102.5 a – 1997.5 a which is 5 a.

Thus, the answer is 0.84 feet, which to the nearest inch is 10 inches. Angle = 1/3956 = 0.0002528 radians = 0.01448° = 0.8690' = 52.14'. One minute = 0.0002909 radians. 1.15075 miles = 6076 feet. Therefore one second will correspond to 101.3 feet. A = l/r = 1.742/5.782 = 0.3013 radians = 17.26° = 17°16'. The angle a is 8.5', which is 0.00247 radians.

So the radius is r = l/a = 50/0.00247 = 20222' = 3.83 miles, nearly four miles. About digits of accuracy. Crawley is careful to give his answers with about the same accuracy as the data in the questions. This is important, especially now that we have calculators.

For example, in problem 1, the datum is 12°28', which has about four digits of accuracy, so the answer, 0.2176, should also be given with only four digits of accuracy. (Note that leading zeros don’t count in figuring digits of accuracy.) An answer of 0.21758438 suggests eight digits of accuracy, and that would be misleading as the given information wasn’t that accurate.

For another example, see problem 3(a). The data are 0°17'48' and 6.2935, with 4 and 5 digits of accuracy, respectively. The answer should, therefore, be given with only 4 digits of accuracy, since the answer can be no more accurate than the least accurate datum. Thus, the answer a calculator might give, namely 0.032586547 should be rounded to four digits (not including the leading zeros) to 0.03259.

Although final answers should be expressed with an appropriate number of digits of accuracy, you should still keep all the digits for intermediate computations.

The lines of sight in angle BAC Expressing horizontal angles 2. Horizontal angles are usually expressed in degrees. A full circle is divided into 360 degrees, abbreviated as 360°. Note from the figure these two particular values:. a 90° angle, called a right angle, is made of two perpendicular lines. The corners of a square are all right angles;.

a 180° angle is made by prolonging a line. In fact, it is the same as a line. Each degree is divided into smaller units:. 1 degree = 60 minutes (60');. 1 minute = 60 seconds (60'). These smaller units, however, can only be measured with high-precision instruments. A circle has 360 degrees Some general rules about angles 4.

A rectangular or a square shape has four straight sides and four interior 90° angles. The sum of these four interior angles is equal to 360°. The sum of the four interior angles of any four-sided shape is also equal to 360°, even if they are not right angles. Lt will be useful for you to remember the general rule that the sum of the interior angles of any polygon (a shape with several sides) is equal to 180° times the number of sides, (N), minus 2,. Right triangle: 90° + 60° + 30° = 180° Choosing the most suitable method 8.

There are only a few ways to measure horizontal angles in the field. The method you use will depend on how accurate a result you need, and on the equipment available.

Table 2 compares various methods and will help you to select the one best suited to your needs. Note:because 90° angles are very important in topographical surveys, the measurement of these angles (used for laying out perpendicular lines) will be discussed in detail. TABLE 2 Horizontal angle measurement methods.

3.1 How to use the graphometer 1. A graphometer is a topographical instrument used to measure horizontal angles. It is made up of a circle graduated in 360° degrees. Around the centre of this circle, a sighting device can turn freely.

This device, called an alidade, makes it possible to create a line of sight that starts from your eyes, passes through the centre of the graduated circle, and ends at the selected landmark or ranging pole. When in use, the graphometer is rested horizontally on a stand. You can build your own graphometer by following the instructions below. It might be a good idea to ask a carpenter to help you. Now build the sighting device, called the mobile alidade. Get a thin wooden ruler, 16 cm long and 3.5 cm wide.

Find its centre, as you did on the board, by drawing on it two diagonal lines from opposite corners. Draw a line through this centre point parallel to the long sides of the ruler. At the same point, drill a hole just a little larger than the diameter of the bolt. Exactly on the central line you have drawn, near each of its ends, drive a thin, headless nail 4 to 5 cm long into the ruler. Be careful not to let the nails break through to the other side of the ruler, and make sure you drive them in vertically. Your alidade is now ready.

Bolt your alidade to the base 11. On the board, along the 0° to 180° line, but outside the graduated circle, drive in two headless nails like the ones placed in the alidade. These will form a second line of sight. Clearly mark the top half of this line of sight with an arrow pointing exactly at the 0° graduation. On one end of the alidade, draw an arrow from the centre-bolt, along the median line, and through the nail at the end. The tip of the arrow should point exactly to the end of the median line above this nail.

This arrow will help you to determine the graduation when you need to read it. Using the graphometer with a stake to steady it Using the home-made graphometer to measure horizontal angles 14. Orient the graphometer with its 0° to 180° sighting line on the left side AB of the angle you need to measure. Position the graphometer so that its centre, the bolt, is exactly above point A on the ground, the station, from which you will measure horizontal angle BAC. For more accuracy, you can plumb-line (see Section 4.8). If you have attached your graphometer by its centre to a stake, drive the pointed end of the stake vertically into the ground at the angle's summit A. Check that the graphometer is as horizontal as possible.

To do this, place a round pencil on the board. If the pencil does not roll off, turn it 90° degrees and check again.

When the pencil does not roll off in either direction, the graphometer is horizontal. Summit A lies behind an obstacle Example You cannot reach summit A to measure angle XAY. On line AX, mark two points B and C. From these points, lay out perpendiculars BZ and CW. On these perpendiculars, measure segments of equal length from line AX, calling them segments BD and CE.

Connect points E and D to form a line, which is parallel to AX. Then extend line ED until it intersects line AY at point F. From a station at point F, measure angle EFY. Its measurement will be the same as that of angle XAY.

XPA, APB and BPC are consecutive angles Example At station P, you have to measure three consecutive angles, XPA, APB and BPC. Take PX (furthest to the left) as the reference line and align the 0° graduation of the graphometer with it. Keeping the graphometer fixed in that position, move the mobile alidade around and measure each angle in turn (in this case, angles XPA = 40°, XPB = 70° and XPC = 85°).

Calculate the consecutive angles as follows: XPA = 40°, as directly measured; APB =XPB -XPA = 70° - 40° = 30°; BPC = XPC - XPB = 85° - 70°= 15°. Then calculate the individual values 3.2 How to use the magnetic compass What is a magnetic compass? A simple magnetic compass is usually a magnetic needle which swings freely on a pivot at the centre of a graduated ring. The magnetic needle orients itself towards the magnetic north. The needle is enclosed in a case with a transparent cover to protect it. Orientation compasses are often mounted on a small rectangular piece of hard transparent plastic.

They have a sighting line in the middle of a movable mirror. If you tilt this mirror, you can see both the compass and the ground line.

A prismatic compass 3. Prismatic compasses give more accurate readings. To use one, hold it in front of your eyes so that you can read its scale. You can see the scale through a lens by means of a prism.

Then turn the compass horizontally until the cross-hair is aligned with the ground mark (an optical illusion makes the hairline appear to continue above the instrument's frame). At the same time, the reading is shown on the compass-graduated circle behind the actual hairline. Since the graduated ring automatically orients itself, the reading directly gives the measure of the angle between magnetic north.

and the line of sight (see also next paragraphs). A magnetic needle always points in the same direction - the magnetic north. This is why compasses are often used for orientation in the field and for mapping surveys (see, for example, Section 7.1 of this manual). The part of the compass needle pointing to the magnetic north is clearly marked, usually in red or a dark colour.

The outside ring of a compass is usually graduated in 360°. The 0° or 360° graduation is marked N, which means north. In most compasses, the graduation increases clockwise and the following letters can be read on the circle:. at 90°, E for east;. at 180°, S for south;. at 270°, W for west.

Intermediate orientations, such as NE, SE, SW and NW, are also shown sometimes. Measuring the azimuth of a line 8. To measure the azimuth of a line, take a position at any point on the line. Holding your compass horizontally, sight at another point on the line, such as a ranging pole. To do this, align the sighting marks of the compass with this point. If necessary (as with some orientation compasses), first align the 0° graduation N exactly with the northern point of the magnetic needle.

At the intersection of the sighting line and the graduated ring, read the azimuth of the line from the point of observation. The reading will be most accurate if you limit the length of the sighting line to 40 to 120 m. Place more ranging poles on the line as you need them.

Note: to check the value of an azimuth, turn around and look in the opposite direction at another point on the same line. Read the measurement of this azimuth, which should differ by 180°. Usually, the difference will not be exactly 180°. If the difference is small enough, you can ignore it, or correct it by averaging the two readings. If it is large, which you should correct. Rear azimuth = 245° Measuring a horizontal angle 9.

To measure a horizontal angle, stand at the angle's summit and measure the azimuth of each of its sides; calculate the value of the angle as follows. If the magnetic north falls outside the angle, calculate the value of the angle between the two lines of sight as equal to the difference between their azimuths. Always subtract the smaller number from the larger one, no matter which azimuth you read first. Just be sure that the magnetic north is not inside the angle.

Example (a) Angle BAC; Az AB = 25°; Az AC = 64°; BAC = 64°- 25° = 39° Angle XAY = Az. If the magnetic north falls inside the angle, the angle between the two lines of sight is equal to 360° minus the difference between their azimuths. To calculate the angle, first find the difference as you did in step 10, above, then subtract this number from 360°.

Example You have to measure angle EAF; measure the azimuth of AE = 23°; measure the azimuth of AF = 310°; angle EAF measures 360° - (310°- 23°) = 73°. Angle EAF = 360° - (Az. AE) Note: to check on your measurements and to improve their accuracy, you should repeat each measurement three times from the same station. These measurements should give similar results. Surveying a polygonal site 13. When you must survey a polygonal.

A Line With Angles

site, measure the azimuth of two sides from each of the summits. For each side of the polygon, you will thus determine one forward and one rear azimuth. You can then check on the accuracy of the two azimuths, which should differ by 180°.

If they do not, subtract 180° from the greatest azimuth and calculate the average between this value and the smallest azimuth. To do this, add the two numbers and divide by two.

From averages like this for the other pairs of azimuths, you can calculate the interior angles of the polygon, as explained above. Note: to make a final check, add all the interior angles. This sum should equal (N - 2) x 180°, N being the polygon (see Section 3.0, step 6). Example You have to survey polygon ABCDEA. From summit A measure forward Az AB = 40° and rear Az AE = 120°. Move clockwise to summit B and measure rear Az BA = 222° and forward Az BC = 110°. Proceed in the same way from the other three summits C, D and E.

In total, you get ten measurements. Mark them down in your notebook. (See columns 1 and 2 where the order of measurements is shown in parentheses.) Calculate the values of column (3) by subtracting 180° from the largest azimuth measured at each summit. This gives you values which should be equal to the smallest observed azimuths, written either in column 1 or in column 2, according to the position of the summit. When the values are equal to the smaller observed azimuths (summits C,E), transfer these measurements to columns 4 or 5, according to the type of azimuth they represent.

When they are not equal (summits A, B, D):. Use columns 1 or 2 and column 3 to calculate the average smallest azimuth.

To do this, add the measurement of the smallest Az from column 1 or 2 to the number in column 3. Divide the total by 2 to find the average. For example at summit A, forward Az AB = (42 + 40) ÷ 2 = 41º. At summit D, rear Az ED = (66 + 68) ÷ 2 = 67º. Enter a forward Az in column 4 and a rear Az in column 5. Add 180° to the smallest calculated azimuths to calculate the remaining azimuths. For example, at summit A, rear Az BA = 41 + 180 = 221º and at summit D, forward Az DE = 67 + 180 = 247º.

As before, enter a forward Az in column (4) and a rear Az in column (5). Check your calculations: the sum of the angles should be equal to (5- 2) x 180º = 540º.

These calculations (79º + 112º + 104º + 118º + 127º = 540º) are correct. 14., proceed as described earlier (see end of Section 3.1). Checking when using a compass When using a magnetic compass to measure horizontal angles, you should carefully check the following points: 15. The magnetic needle must swing freely on its pivot.

Keep the compass horizontal in one hand and, with the other hand, bring an iron object close to the magnetized needle's point. Make the needle move to the left with the iron; when you move the iron away, the needle should swing quickly and smoothly to its original position. Repeat the movement in the opposite direction to double check.

Then pull it away. The needle should swing back into place 16. The magnetic needle must be horizontal when the compass is horizontal. Lay the compass on a horizontal wooden surface (such as a table) and check that the needle remains horizontal. If it does not, you will have to open the case of the compass and add a light weight to the needle. To do this, you can wind some cotton sewing thread around the part of the needle that is highest, and move the thread back and forth until the needle is balanced and horizontal. Do not keep iron objects close to the compass.

Iron will attract the magnetic needle, and your measurements will be wrong. Distance measuring lines made of metal, such as steel bands, steel tapes and chains, as well as metal ranging poles and marking pins, should be kept 4 to 5 m away from the compass when you are measuring angles. If you wear eyeglasses with metal frames, you will also have to keep them away from the compass. Remember that concrete structures (towers, bridges, etc.) are built with iron bars which may also cause the compass needle to move.

Do not use a compass when there is thunder. It affects the needle. Do not use a compass near an electric power line. Keep the compass horizontal while you are measuring with it. Note: because the magnetic needle of the compass is always affected by the presence of iron nearby, checking the measured azimuths (as explained earlier) is extremely important. If your results do not agree after repeated measurements, local magnetic disturbances caused by the presence of iron in the ground may be responsible for the errors. You should then use another method of measurement.

3.3 Graphic methods for measuring horizontal angles To use the graphic methods for measuring horizontal angles, you need to draw the angle on paper first. Then you will measure the angle with a protractor (see step 11, below).

As you have seen with other methods, you can obtain more accurate results if you repeat the procedure at least twice to discover possible errors. Using a simple compass and a protractor in the field 1.

With this method, you can The only purpose of this compass is to show the direction of the magnetic north. Get a 30 x 30 cm piece of stiff cardboard or thin wooden board, and several sheets of square-ruled paper (such as millimetric paper).

Lightly glue each sheet, at its four corners, to the board, one on top of the other. On the upper left-hand corner of the top sheet, attach the compass, for example with a string or rubber band or within a small wooden frame, so that its 0º to 180º reference line is parallel to one of the rules on the paper. With a pencil, draw an arrow straight up toward the top of the sheet, and mark it North. To draw the horizontal angle BAC you need to measure, stand at the angle's summit A and look at aground line AB which forms one of the sides of the angle.

Keeping your board horizontal on the palm of one hand held in front of you, turn it slowly around until the northern point of the compass needle reaches the 0°-graduation Your sheet of paper is now oriented, with its arrow facing north. Note: it will be easier if you rest the board on a stable support, such as a wooden pole driven into the ground. Then sight and draw line ac 8. Using a protractor (see steps 15 to 17 below), measure the azimuths of the lines you have traced as the angles formed by them with any of the paper rules running parallel to the north. Remember to measure the angle clockwise from the north to the pencil line (see Section 3.2).

Note: you only need to measure angles smaller than 90º, since the square-ruled paper shows the 90°, 180º and 270º directions. Take the azimuths of the two sides of the horizontal angle, and in Section 3.2. Using a plane-table and a protractor 10.

(see Section 7.5), you can use it to draw the angles on paper while you are in the field. Then it is easy to measure them with a protractor (see steps 15 to 17, below). What is a protractor? A protractor is a small instrument used in drawing. It is graduated in degrees or fractions of degrees. The semicircular protractor is the most common type, but a full-circle protractor may be best for measuring angles greater than 180º. Protractors are usually made of plastic or even paper.

You can buy one cheaply in stores that sell school supplies. Or you can use the one provided in. Either make a copy of it, or copy it on to transparent tracing paper.

Note that the arrow points at the exact position of the protractor's centre. 50 3.5 How to measure horizontal angles with a theodolite What is a theodolite? A theodolite, sometimes called a transit, is an expensive instrument which surveyors use to measure horizontal angles precisely., but more complicated (see Section 3.1). Most theodolites are designed to measure vertical angles as well. The theodolite's basic features for measuring horizontal angles are:. a horizontal circle, graduated in degrees, which may be rotated and then clamped in any position;.

a circular plate which may be rotated inside this circle, and which shows additional graduations for reading the graduations on the circle with greater precision;. a telescope which is attached to this circular plate and turns with it, and which can also be turned up and down in the vertical plane. a tripod (three-legged support) on which to place the theodolite when measuring. Setting out a perpendicular by the mid-point method 16. The easiest way of setting out a perpendicular from a fixed point A on line XY is to use a simple line clearly marked at its mid-point with, for example, a knot.

This line can be a liana, a rope or a string or you may use a measuring tape, whose graduations will help you to locate the exact mid-point. For good results, the line should be at least 8 m long. A longer line will make your measurements even more accurate. If you are working alone, make a small loop at each end of the line. Setting out a perpendicular by the intersection method 20. To set out a perpendicular by the intersection method, you can use a simple line again.

The method you use will depend on the length of the line. Remember that:. if the perpendicular is to be short, it is best to use the first method (steps 21-29);. if the perpendicular is to be long, it is best (steps 30-38). Using the short-line intersection method 21. To use this method, you will need a simple measuring line such as a liana or a rope 5 to 6 m long, a short pointed stick or thin piece of metal (such as a big nail) and five marking stakes. Set out line XY.

On this line, choose point A, from which you will set out the perpendicular, and mark it clearly with a stake. With part of your measuring line, measure a 2 to 3 m distance to the left of point A on XY. Mark this point B with a stake. Measure the same distance on XY to the right of point A. Mark this point C with a stake. Make a fixed loop at one end of your line, and securely attach the pointed stick or piece of metal to the other end. Place this loop around marking stake B.

Then, keeping the line well-stretched, trace a large arc on the ground with the other end of the line. This arc should extend beyond point A, and a long way on either side of XY. Take up the loop from stake B and place it around stake C. Trace another arc on the ground which should intersect the first arc at two points, D and E. Clearly mark these two points D and E with stakes. Using the long-line intersection method 30.

To use this method, you will need a simple line about 55 m long, a short pointed stick or thin piece of metal and four marking stakes. Clearly mark point A on line XY with a stake.

You will set out the perpendicular from this point. Measure 25 to 30 m to the left of point A on line XY, using part of your measuring line; mark this point B with a stake. Measure the same distance on XY to the right of A; mark this point C with a stake. Make a fixed loop at one end of your line. Securely attach the pointed stick or piece of metal to the other end of the line (as in step 25, above). Place the loop around marking stake B and, with the other end of the line in one hand, walk diagonally away from line XY. When you reach a point above A where the line is well stretched, trace an arc 2 to 3 m long on the ground with the end of your line.

Repeat the last step from the second stake C. The arc you mark on the ground from this point should intersect the first arc at point D.

At this intersection point D, drive a marking stake into the ground. The line AD joining D with the original point A is perpendicular to XY. Note: you can only use the intersection method on ground that is clear of large rocks and high vegetation, because you must be able to mark and see the arcs easily. If necessary, you can clear the ground as you work. Setting out a perpendicular by the 3:4:5 rule method 39.

The 3:4:5 rule is that any triangle with sides in the proportion 3:4:5 has a right angle opposite the longest side. The method is based on this rule. The length of the simple line you use for measuring will depend on the length of the perpendicular you are setting out.

The longer the perpendicular, the longer your measuring line must be. Examples.

Very short line: about 1.5 m long, a little longer than 0.3 m + 0.4 m + 0.5 m = 1.2 m;. Short line: about 13 m long, a little longer than 3 m + 4 m + 5 m = 12 m;. Medium line: about 38 m long, a little longer than 9 m + 12 m + 15 m = 36 m;. Long line: about 65 m long, a little longer than 15 m + 20 m + 25 m = 60 m. To make your simple line, get a rope 1-1.5 cm thick; it is best if made from natural fibres which will stretch or shrink very little. A piece of used sisal rope will stretch or shrink less than a new one. You can also use a measuring tape.

There are several ways of using the 3:4:5 rule method, depending on the type of measuring line you use and the number of people who can work together with you. When using medium or long lines, it is best to work in a team of three people. When using a short or very short line, you can work by yourself. Making your own 3:4:5 measuring line 42. You can easily make a simple line to use with the 3:4:5 rule method.

This line is sometimes known as a ratio rope. The following shows one way of making a short line about 13 m long, but you can make shorter or longer lines in the same way. Take a piece of rope about 13 m long.

A few centimetres from one end, tie a metal ring to it securely with heavy string. Note: you can also use a 3:4:5 ratio rope with much shorter segments. A 30 cm: 40 cm: 50 cm line, for example, is ideal for measuring angles of smaller areas, which can be used for laying out a V-knotch weir, for example (see Vol.4, Water, Section 3.6). Using the medium 3:4:5 line to set out a right angle 53. Use a line about 36 m long, prepared like the short line, except that the sections should be 9 m, 12 m and 15 m long.

Starting at point A, where the right angle has to be set out, stretch the 12 m segment along line XY; at this point attach the ring on the line to stake B. With the 15 m segment, walk away from B while your assistant returns to the original point A with the 9 m segment of the line. When these last two sides of the triangle are fully stretched, mark the point C which connects the 9 m and 15 m lengths. This point forms perpendicular AC at A. Setting out a perpendicular with a cross-staff 63. A cross-staff is an inexpensive sighting instrument which is very useful for setting out right angles. There are several models, such as the octagonal brass cross-staff, which has sighting slits cut at right angles to each other, and the foresight/backsight model.

In use, cross-staffs must be firmly fastened to a support, usually a stake driven vertically into the ground. Their useful range does not extend beyond 30 to 40 m. You might be able to borrow a cross-staff from a surveyor's office, or you can build your own as described below.

Note: the octagonal cross-staff also has additional sighting slits cut at 45°, and is useful for setting out 45-degree angles (see, for example, Section 2.9, step 7). Adjusting the home-made cross-staff 67. Lay out a right angle on the ground (see steps 56 to 59, this section). The sides of the triangle will be next 15 m, 20 m and 25 m long. Put a short stake at point A, the corner of the right angle, between the 15 m and 20 m sides. Then put ranging poles at points B and C to mark the sides of the angle.

Position the cross-staff and its vertical support at point A. Align one cross-piece alongside AB and sight towards point E.

Without moving the vertical support, align the second cross-piece along the other side AC of the angle, and sight towards point C. Tighten the screws a little to keep the cross-pieces in place. Sight at point C with the other one and tighten the screw 72. Rotate the vertical support 90º to check that the cross-pieces are truly at a right angle. Sight at points B and C again and correct the position of the cross-pieces if necessary.

Repeat this process until you are sure that each cross-piece is aligned with one side of the right angle, that is, that they are at 90° angles from each other. When both cross-pieces are properly aligned, firmly tighten the screw holding them to the vertical support. Check both sighting lines again after tightening the screw to make sure that the cross-pieces have not slipped. To help you adjust the cross-pieces later, cut or engrave (with a large nail) marks in the wood or metal of the bottom cross-piece when the top piece is in position. Mark the lower cross-piece for reference Using the cross-staff to set out a right angle 77. To use the cross-staff, you will need an assistant. Lay out straight line XY on which you need to construct the right angle at point A.

Place the support of the cross-staff in a vertical position at point A. Ask your assistant to hold a ranging pole in a vertical position at point B, near the end of XY.

Sight along one of the cross-pieces and rotate the vertical support until the sighting line is aligned on B. Without moving the cross-staff and its vertical support, sight along the other cross-piece. At the same time, direct your assistant to stand with a ranging pole as near to this sighting line as possible. BAC is a right angle Note: with the help of a cross-staff you can easily determine the rectangular areas which you need for a fish- pond lay out. You can also build a grid of squares by determining intermediate angles along your straight lines. This is a method used in estimating reservoir volumes, for example (Volume 4, Water, Section 4.2).

3.7 How to set out parallel lines What are parallel lines? Parallel lines, also called parallels, are lines equally distant from each other at every point. Parallel lines run side by side and will never cross. They are very important in fish culture and are often used in designing fish- farms (for example, for parallel dikes and ponds), in building dams and in setting out water canals. Parallels are also useful when (see Section 1.7).

Setting out parallels by the 3:4:5 rule One way to set out a parallel line uses the 3:4:5 rule. It works like this: 2. On given line XY, select two points A and B which are fairly distant from each other (for example, 20 to 30 m apart), and mark them with pegs. From each of these points, using the 3:4:5 rule method. Remember that the length of the line you will use depends on the length of the perpendicular you are setting out (see Section 3.6, step 35).

Prolong these two perpendiculars as required. Then, measure an equal distance from the given line XY on each of them; mark these two points C and D. Through these two points, set out a line WZ.

This line will be parallel to XY. Connect the points to form the parallel. Setting out parallels with the crossing-lines method To use the crossing-lines method, you do not need to set out perpendiculars; you will only measure distances.

However, this method cannot be used when you need to measure the exact position of the parallel you need to set out. It is useful when the distance of the parallel is not important, such as when you are (see Section 1.7). Proceed as follows: 6. Lay out line XY. Select any point A which will belong to the parallel line you need to set out. Clearly mark point A with a peg.

Clearly set out line WZ through points F and G using ranging poles. Starting from point B on line XY, measure intermediate distances BE, EC and CD. Then move back to line WZ; starting from point G, measure intermediate distances GH, HI and IJ equal to BE, EC and CD, respectively. Mark points H, I and J with pegs.

While you are doing this, check that point I falls exactly on the intermediate perpendicular set out from C. If there is a small difference, adjust the positions of the perpendicular and point I. If there is a large difference, check your previous work for errors. As a final check, be sure that the last measurement JF lines up with point F.